|

Coach Tigran strip coaching Irene Yeu (who took 5th) at the World Cup in Bratislava. The Coach, Part 1

The Importance of Strip Coaching The relationship between the fencer and coach can be one of the most important relationships of your child’s young life. And a relationship that can last through college and beyond. This relationship will be based on many different elements, and will evolve accordingly. I think the basis of the relationship is goal oriented. What does your child want to achieve in fencing? What do you want your child to achieve? Once you understand that, the relationship with the coach will be somewhat defined by that. And those goals can change and evolve as your child grows and matures and is more able to be involved in those kinds of decisions. My son and I have gone from the goal of “being more confident and assertive” to “making the World Cup Cadet Team.” As you can imagine, the role of the coach in my son’s life has dramatically changed. And their relationship has evolved, As in any successful relationship, communication is key. Your fencer and coach will learn, through trial and error, how to best communicate with each other. Lessons, classes, competitions, strip coaching, and eventually traveling together internationally, are all building blocks in this relationship. Strip Coaching: During the two one-minute breaks that occur in 15-touch bouts, the "strip coach" will go onto the strip and coach the fencer, offer tips on strategy, suggests tactics. A strip coach is also a valuable extra pair of eyes to look for weaknesses in his student's opponent, which he can then pass on to his student. Strip coaches can also offer suggestions between touches, quick little reminders to "keep it small," etc. Strip coaching is an important element of building this relationship, and an important part of fencing and learning to compete, regardless of what your goals are. Strip coaching is also an important element in terms of helping your child develop confidence, learn strategy, sportsmanship, how to stay focused under pressure, and also can help make competing a positive experience. The Role of Strip Coaching in the Grand Scheme of Things Parents frequently ask me questions about strip coaching. The question asked most frequently is, “Do they really need it?” My answer - “Yes.” And also, “Not always, it depends on the circumstances.” Let me explain. Yes. If your child is just starting to compete, he will probably feel some pressure to succeed. And she can feel overwhelmed by just the visual sea of white uniforms, the noise of the scoring machines, and the cheering (and less positive sounds, unfortunately) of parents and coaches around them. It can be hard to focus. Your fencer has probably been taking classes and private lessons for at least three months, although my son did not start competing until after over a year of classes and private lessons. Now, suddenly, this is it. All of those classes and lessons come down to this moment on the strip. What happens? More often than not, if he is young, your fencer will forget everything he has been working on. He will forget his footwork. She might even forget to fence. True. I have seen my son, early in his competing and bewildered on the strip, forget to hold up his sword. Or, facing a new, unknown adversary, your young fencer might just walk off the end of the strip rather than defend himself, another move my son seemed to favor in the beginning. Young fencers often have trouble figuring out exactly where the end of the strip even is. In the midst of what can be an overwhelming and confusing experience, the familiar voice of his coach, by his side, reminding him what to do, encouraging him, can make all the difference in the world. A coach on the side warning him that he is almost off the strip is very helpful. “Move in and out,” he might suggest. “Keep moving your feet.” And your child nods, mask wobbling a bit because she hasn’t quite grown into it yet, and she is able to refocus on what is in front of her. Her coach gives her a sense of confidence. “Oh, yeah,” your fencer thinks, “keep moving my feet. I know this.” And maybe a touch is scored, and your fencer nods again and thinks, “I can do this.” This helps build confidence and keep the tournament experience positive. Your coach also learns a lot about your fencer at a tournament. Your coach learns how your fencer responds to pressure. Your coach sees what training goes out the window first, no lunge for example, and so will probably focus on that in the next few lessons. Your coach will find out whether your fencer is able to listen to direction, and follow through on suggestions. All of this experience will help your coach work better with your child, and help your child do better on the strip. These are important building blocks and help create a foundation for your fencer and also for the relationship he or she will have with the coach. Different fencers need different things from strip coaching. Some fencers want a variety of suggestions from the coach, some want to be told exactly what to do. Some want to figure it out for themselves, and need the coach there for support and for that very important debriefing after the bout is over. As your fencer matures, as he and the coach work together, they develop an understanding of what is most successful and their own unique relationship evolves. As a parent, I have found it important to respect that evolution, and to support it by not interjecting myself into it. I trust our coach completely. I might not always agree with him, but I am not the coach. I don’t undermine the relationship they are creating. I defer to him on all things coaching. How to support your strip coach- 1. Be quiet Believe it or not, your coach needs a lot from you when he coaches your fencer. He needs you to support him. What does this mean? Often, in the heat of the moment, I have seen parents jump in and yell directions from strip-side. My advice, don’t say anything, other than “Good job!” or words of encouragement when your fencer scores a touch. You can be supportive of your fencer without actually telling them what to do. There are a few reasons why I recommend this.

2. Communicate with your coach. Chances are your coach will be coaching several fencers in the same event. And sometimes, there are two events that overlap, so the coach is even more frazzled. Your job in supporting both your coach and your fencer is to let the coach know when your fencer is fencing.

I am often surprised by parents who don’t want strip coaching at the national level. Usually, this seems to center round a concern about the expense. Here is my take on this - you have invested in classes, lessons, equipment, and if you are going to a NAC, you are now including travel, flights, hotels, rides to and from the airport, food… And let’s not forget the investment of time itself. Not just the classes and lessons, but the travel to and from the studio, travel time to the tournaments, etc. At a NAC, the pressure is really on. Fencers are after medals and points. Why wouldn’t you want to invest in having someone who knows your fencer’s abilities, strengths and weaknesses, strip side to guide him or her to do the best they are capable of? This expense is where you might draw the line? This is the time, I think, that you might want to make sure your fencer has all of the support possible. A word about sharing a coach with fellow fencers from your club. Coaches are there to support all of their fencers. How do coaches decide who is coaching which fencer? At Swords we often have two or more coaches who divide up the fencers among them. This division is based usually on two things. Who is the most familiar with a fencer’s style and abilities? And where are the fencers fencing? If two coaches are covering six fencers, they will probably divide up the fencers primarily based on their strip locations. Sometimes at national events, one fencer will find himself in a completely different room on a different floor even. You don’t want coaches to end up running all the way across the venue to support two different fencers. They will be exhausted and chances are, they will most likely miss some of the bouts. I have seen our coaches, standing together when pools are announced, deciding which coach will help which fencer, and almost always, those two factors are the deciding ones. There are all kinds of challenges that coaches end up facing, and often, how the coaching is divvied up depends on basic logistics. It’s nothing personal. Coaches want all of their fencers to succeed. Now - for the second answer - “Not always, it depends on the circumstances.” A couple of years ago, Stafford went through a sort of slump. When he was fencing and fell behind, he got frustrated and emotional. When he was ahead, he might freeze. If the coach was late arriving strip side, he might panic, as if he didn’t know what to do, and couldn’t do it on his own. So… I signed him up for almost every single RYC and RJCC available. We went to many of these without a strip coach. Just to get him to deal with his emotions and frustrations on his own. I hoped he would break through and, perhaps out of sheer exhaustion from competing almost every weekend, just fence and not get emotional. For the most part, it worked. Another reason you might not always want a strip coach is because I do think it is important for your fencer, as he gets older, to start to figure out for himself what strategies might work in any given circumstance. Fencers need skill, strategy, and stamina. You might want to take advantage of some of the local and regional tournaments to give your fencer the experience of thinking on his own on the strip, trying things and maybe failing, but the trying is the important thing. I don’t recommend this for National tournaments - again, you have invested a lot in those, so give your fencer every advantage you can, so she can perform to the best of her abilities and have, win or lose, a successful experience.

6 Comments

What is a referee?

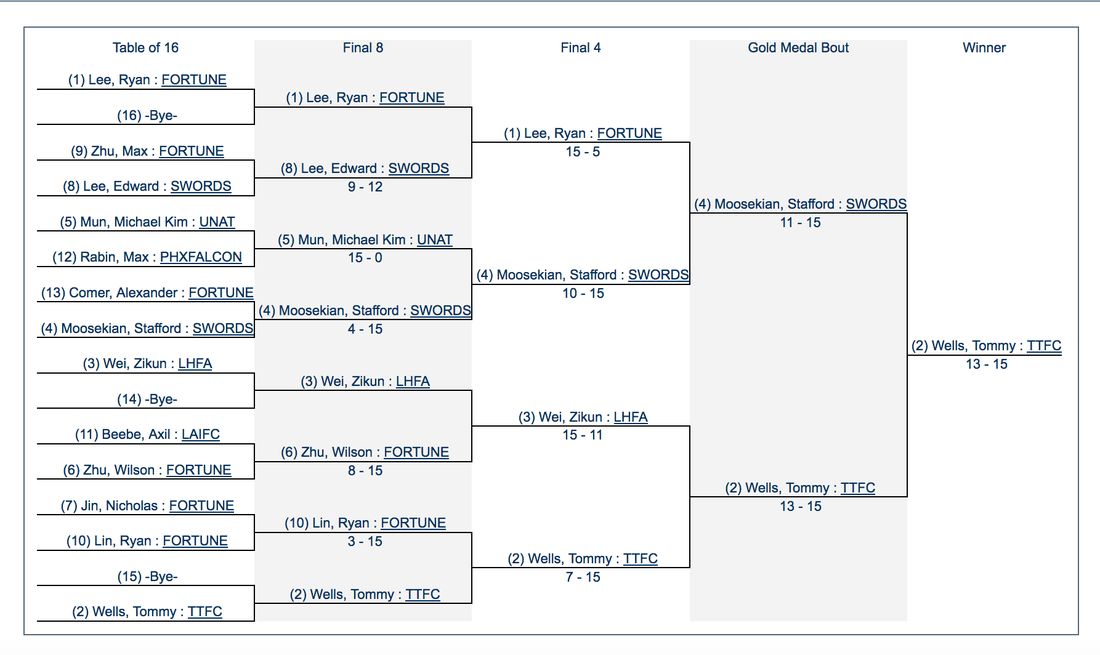

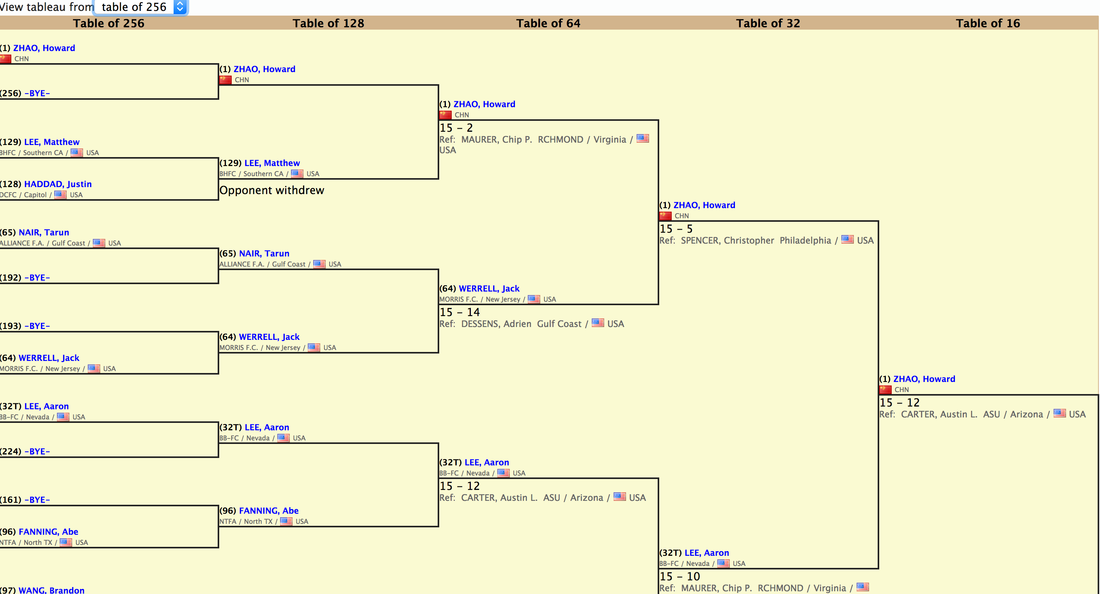

The referee is the person of authority in a variety of sports who is responsible for presiding over the game from a neutral point of view and making on-the-fly decisions that enforce the rules of the sport, including sportsmanship decisions such as ejection. – Wikipedia I love that this definition mentions sportsmanship. Fencing emphasizes sportsmanship in so many ways. I value this emphasis on sportsmanship, and believe it is important for my son to understand what sportsmanship really means. Sportsmanship is an aspiration or ethos that a sport or activity will be enjoyed for its own sake, with proper consideration for fairness, ethics, respect, and a sense of fellowship with one's competitors. There is a reason why a fencer salutes the referee at the beginning of the bout. And why a fencer shakes hands with the referee at the conclusion of the bout. These gestures, the salute and the handshake, signify the respect that the fencer must show throughout the bout, to his opponent, the ref, and the sport itself. The salute to the ref at the beginning is recognition of the role the ref plays, and the authority he has on the strip. The handshake at the end means, “Thank you. I respect the work you did enforcing the rules and presiding over the bout.” I appreciate that there is a dress code for referees, in sort of the same way that there is a uniform for fencers. Referees almost always dress well, a coat and tie for men, a skirt or slacks for women. This shows an attitude of respect towards the sport, the fencers, and the important role the referee plays in the world of fencing. Who are these referees? They are you. Fencing referees are mostly fencers who got involved in refereeing or fencing parents who got involved in refereeing. Several fencing parents who started refereeing, either to help (a small amount) with the expense of fencing, or because they wanted something to do while at tournaments with their fencers, have continued to referee long after their fencers have left for college or even left the sport of fencing altogether. They enjoy the sport, the people, and the travel. They get paid very little. No ref is in this for the money. Some referees have had amazing fencing careers. Some referees have never fenced. it’s not necessary to have any previous experience as a fencer before becoming a ref. George Porter, for example, is one of the top refs in our Division, yet he never competed as a fencer. If you are standing behind a referee in the security line at the airport on the way to a NAC, or checking in at a hotel, if you find yourself getting into an elevator with one, introduce yourself and say, “Hello.” They appreciate it. And they have a lot they can teach parents and fencers, and some great stories. You will discover, as your fencer competes, that you will see the same refs at many different tournaments. Some of the local refs are also refereeing on the national and international level. If they are on the international circuit, they have gone through a lot of training and have a lot of experience. Often, the lesser experienced are reffing in local tournaments, getting a sense of what goes into refereeing, making the calls, defending calls, and learning to interpret the rules. Older fencers will often have their first reffing experience at their own club, refereeing younger fencers at an unrated tournament. Much like young fencers learning how to fence, you may also encounter young referees on your fencer’s strip, learning how to ref. Be patient with these kids. They might grow into great referees. Support them. Don’t yell at them or argue with them heatedly. If you have a question about a call, ask it. And then listen, respectfully, to the explanation. But don’t humiliate the young ref, berate him, or chastise her. If it is a misunderstanding of a rule, if for example, you think the young ref has misunderstood the meaning of “one action” for example, talk to the bout committee (quietly) after the bout is over, and suggest that someone might want to review that particular rule with the ref. You might also discover that, in fact, you were the one who has misunderstood the rule - another good reason not to get upset in front of your fencer and make a scene. Also, if you have a problem with a young referee reffing your fencer’s bout, say if it is a semifinal of an RYC, for example, prior to the bout, you can go to the bout committee and voice your concerns about his or her experience at this level of competition. Otherwise, do your part in helping to encourage the ref. Support his or her efforts, recognizing that he might be nervous, or she might be shy. The Referee and Your Fencer’s Safety Believe it or not, one of the referee’s tasks is to make sure that your fencer is safe. This means not just those tricky corps a corps calls, but also making sure jackets are zipped up, mask bibs are down, shoes are tied, etc. The referee understands that a hole in a sock could potentially catch a sword tip and cause some serious physical damage. I have been sent on a frantic search for a safety pin because the Velcro on the jacket is no longer working. I wasn’t happy about it, but I recognized that it was a safety issue, not that the ref was trying to keep my son from fencing. (By the way, I always have a safety pin or two with me, now.) If a referee asks that something be fixed on a uniform, fix it. And thank him. ‘Ball and Strike” Calls Like a baseball umpire, a fencing referee has to make judgment calls on many rulings that are close (can be decided either way). As an example, what one referee would call “simple and immediate” (the one action rule), another would determine as not completed in one motion or too late after the opponent went out of the strip. The rule itself may be clear (just like the strike zone in baseball), but a quick, definitive ruling (which is required) on a close call will often get one set of fencer, coach and parents outraged. Every batter striking out feels that the pitch was out of the strike zone, and every pitcher walking a batter feels that the pitch was right-down-the-middle — when a ruling can go either way, depending on the referee, one will be right and the other will be wrong. That’s sports. I think refs appreciate it when fencers acknowledge touches that are questionable (like that ‘floor’ touch that you know really hit your foot). Likewise, fencers should inform the ref if they think they were awarded a touch that they really didn’t deserve (e.g., getting a point for hitting the floor and the ref awarded it as a toe touch). This is a sign of good sportsmanship. Eventually, you will probably see all of the top fencers do this. They understand, after years of competing, that winning is important but it is also important how you win. Bias There are specific guidelines restricting a referee from directing a bout that he/she may have conflicting interests in (same club, relationship, etc.). Generally speaking, a referee directing a bout does not see the individual fencers, but only the fencing actions. Thus, fencers should recognize that a call, even a wrong call, was based on what the referee believed he/she saw in the sequence between “fence” and “halt” — not who a fencer is. If there are legitimate questions of bias, those should be addressed with the bout committee, of course. But, mistakes by a referee sometimes happen during fast and pressure-filled action, just like a fencer’s own fencing is not perfect in such circumstances either. Referee as Teacher I have seen wonderful lessons in action watching interactions between some referees and fencers. One young fencer gave his opponent the finger on the strip. Black card. Which is of course the appropriate response. But that wasn’t the end of the story. A black card certainly got the point (slight pun there) across, but this wonderful referee went a bit further. He had the fencer sit next to him at the bout committee table for the rest of the event, as fencers checked in for other events, returned bout slips, etc. and gave him some wonderful lessons about how the tournament works, scoring, and other advice. I love the March NAC because it is focused on the younger fencers, Y10, Y12, and Y14 only. This is the first NAC for many fencers and a learning experience in so many ways. The referees know this too. Often, they take extra time to explain to the fencers some of the rules and expectations. I’ve seen a ref explain how pool bouts work and how important it is for a fencer to listen for his name and to be ready. You can literally see fencers growing in confidence from the first day of check in to the final day of competition. The referee has a lot to do with this transformation. A referee can ref your fencer’s bouts for years, showing up at local, regional, national, and even international events. And referees get to know the fencers. They watch with genuine interest as fencers become successful and they want fencers to succeed. Attend a Referee Clinic If you really want to understand some of the finer, more intricate points of fencing calls and reffing, attend a clinic. And have your fencer do one as well. You will learn so much. It is a complicated sport. And all three weapons have very different rules. Once you start to be able to see some of the finer points of fencing in action, (in epee that might be passing or one action for example), you will have more appreciation for the role the referee plays in the life of the bout on the strip. Once you put yourself in the position of making calls, and having people around you disagree with you, you will have more empathy for the ref. And, who knows, you might decide, like many other parents, that you enjoy reffing and being a part of this wonderful world of fencing, competition and sportsmanship. Fencers should all be a referee for at least one tournament (many local tournaments have self-ref opportunities). When a fencer experiences making difficult judgment calls as a referee, he/she comes to the realization that refereeing a bout is not easy. In every difficult or “close” call, each fencer feels strongly that the ruling should be in his/her favor, resulting in one side being convinced that the referee made the wrong ruling. Respecting the Referee I recently heard two things that I found disturbing. · Parents received red cards at Summer Nationals for yelling at the referee. · People no longer want to referee because of the abuse they take from parents strip-side (not coaches, parents). If I knew one of these parents, I might suggest to him or her, please tell your child you made a mistake. That you respect the system, the referees, and the sport, and that you got caught up in the heat of battle, and you acted inappropriately. Your child needs to know that you are willing to admit when you make a mistake. Even if you know the call was wrong, you need to show that you respect the authority of the referee making the call. That is what this is about. Not about who was right and who was wrong about the call. At the end of the day, the referee makes the call. It is his or her strip, and the call is dependent on what the ref saw. Not what the parent saw. And don’t ask the ref to review the footage you just shot of the point, proving that the other fencer was off the strip, or the touch hit the floor not your child’s toe. It doesn’t matter. All that matters is what the ref saw. And modeling sportsmanship means that you respect that. And you teach your child to respect that. There will be bad calls. There will be those details the ref didn’t see, or that he saw differently. That is just a fact. It will happen. It happens in other sports, too. Deal with it. And model the appropriate behavior for your child. Because one of these days, you won’t be strip-side and your fencer will model your behavior and will get a black card. Teach your child by modeling the kind of behavior that will help your child be successful and strengthen your child’s understanding of sportsmanship. Regardless of whether a referee is new to the position or has been reffing for years, all referees deserve the respect that sportsmanship demands. Does that mean you should not question a call? Of course not. But ask yourself, are you questioning a call for a legitimate reason, or because you want your fencer to win? And how are you questioning the call? Are you asking why a particular call was made, or what it was based on? And, after the briefest of moments, because you are interrupting the rhythm of the bout, the focus of the fencers, etc., are you graciously accepting the call after it was explained to you, or perhaps though still respectfully disagreeing, nevertheless allowing the referee to continue to do his or her job, respecting his or her authority? Or are you angry and accusing, saying that the referee is blind, made a bad call, is an idiot, etc.? Are you using offensive language? That also sends a powerful message to your child. Good sportsmanship is a part of developing life skills such as a sense of fairness, consideration of others, respect for authority, fellow competitors, oneself, and the sport, fair play, dealing with adversity and failure, discipline, responsibility, goal setting, and honor. The relationship your fencer develops with referees will be indicative of his or her sense of sportsmanship, and can set the tone for years of competing. Your child is not just learning how to fence. Your child is learning about himself or herself in so many different ways, learning how to successfully participate in the world. As a parent, show him how it’s done. Shortage of Referees There is a shortage of available referees in the sport. Why? Low pay, long hours, weekend work are not the only reasons for the lack of enough referees. Most referees participate to support the kids and support the sport; but referees often do not receive the equivalent support from the fencers and the fencing governing body. And without referees, the sport of fencing cannot survive. The Tournament - Part Three - Direct Elimination Promotion: In Y10, Y12, and Y14, all fencers in all tournaments, regardless of how well they did in pools, move on, or are promoted to the Direct Elimination round. In Cadet and Junior national and international events, the bottom 20% of fencers out of pools are eliminated and do not move on to the next round. Direct Elimination Seeding: Direct elimination placement is based on the results of the pool bouts. The number one seeded fencer out of pools – the fencer who won the most of his bouts would be the fencer who won the highest percentage of his pool bouts with the highest number of indicator points. He would be ranked number one- and at the very top of the tableau. (Tableau is the break down of the elimination round. Each round in the tableau is called a table. The rounds are tables of: 512 / 256 / 128 / 64 / 32 / 16 / 8 / 4 /2. ) The fencer seeded number two out of pools would be at the very bottom of the tableau. Starting with the smaller, local tournament, using the example from the Pools blog, there were 13 fencers, so looking at the tableau, it starts at table of 16 (16 slots), with three fencers getting a bye to the next round. Take a look: Because this tournament is finished, you can see the score of each bout. The first score is always the top name, the second score, the bottom name. So, in the final, Tommy Wells beat Stafford Moosekian, and the score was Tommy 15- Stafford 13. Now let’s go on to the more complicated Cadet event from the same blog. Because this event was a national event, 20% of the fencers were eliminated, so only the top 130 advanced to the Direct Eliminations. The 130 fencers are then divided into pods, based on seeding. Only 2 fencers, who placed 127, 128, 129, and 130, did not receive a bye into the next level – 128. Typically, the fencer who is seeded second out of pools is at the very bottom of the tableau, the idea being that the top two fencers eventually meet each other in the final round. Here is the top section of the Direct Elimination round: The tableau is made of up all the fencers divided into groups of fencers called pods. Fencers will first face fencers within their pod. If your fencer wins the pod, he or she will next face the winner from another pod. In this event, there were 4 pods, and each pod consisted of 33 fencers. (The photo above shows only a part of the pod.) The quarter finals or the semi finals, depending on the size of the tournament, will be the top fencers from each pod facing another. So pod 1 faces pod 2, and pod 3 faces pod 4, etc.

Each Direct Elimination bout goes to 15 touches, with three periods that last three minutes each. There is a one minute break between each period, so two breaks per bout. ( Y10 events only go to 10 touches.) The bout ends when either a fencer reaches 15 touches, or the time runs out. In the event of a tie at the end of the final period, there is a one minute extended period, during which either fencer can score a final touch. In this situation, double touches do not count. At the beginning of this extended period, there is an electronic coin toss - a random mechanical assignment of “priority” which means that if neither fencer scores a touch, the fencer who was awarded “priority” wins. During the one minute rest, fencers often get a quick visit from the coach and a chance to get a drink. Fencers should bring a bottle of water, gatorade, etc., to the strip or have someone stripside with something, as fencers are not allowed to leave the strip until the bout is over. Fencers should salute the opponent and referee at the beginning and end of each period. This blog is about Direct Eliminations and how they work. However, there are a lot of rules that fencers need to be aware of, as well as a code of conduct on the strip that must be followed. Sometimes a fencer might want to question a ref’s call which is fine, but it should be done respectfully. Fencing rules can be found in the rules handbook, and with experience, fencers will learn what they are, remember them, and in some cases, use them to gain advantage. Happy fencing! Addendum: This very useful information for determining a fencer’s Direct Elimination opponent was provide to us by Fencing Dad. Thanks, Fencing Dad! Great article! For the impatient fencers: Kids often want to know who they are going to fence when the seedings come out after the pools (but before the tableau is posted). The formula is the following: Table (minus) your Seed (plus) one. So, if there are 17 fencers and you are seeded 16th after pools, here is the calculation: 32 (table) – 16 (your seed) + 1 = 17 (your opponent). So, you fence the 17th seed. (The winner of that match means you are in the next table — so, 16 (table) – 16 (winner of the match takes the better seeded seat) + 1 = 1 (thus, the winner of 16th vs 17th will fence the 1st seed). Another example: If you are seeded 15th after pools, it is 32 – 15 + 1 = 18 (since no one is 18th seed, you have no one to fence, so you get a bye; then go down to the next table: 16 (next table) – 15 + 1 = 2 — so, you will fence the 2nd seed. How exactly does a tournament event work? An event in a fencing tournament consists of two parts, the first - Pools, and the second part, Direct Eliminations, which is based on the outcome of the pools. Time: One of the biggest questions that new fencing families have is how long will an event take? My experience? If there are over 30 fencers, plan to be at the event all day. If there are less than 30 fencers, plan for at least three hours. There can be all kinds of delays, some small, some huge. An example of a small delay, at a small tournament, a fencer who has signed up is caught in traffic and because he has called ahead and is making all efforts to arrive on time, the organizers agree to hold the close of registration a few more minutes. A large delay? Sometimes, at larger tournaments, if there are not enough referees or strips, pools can be flighted. This means the pools will be divided into two groups. The first group will begin at the original, announced time and the second group will either begin at a later specified time, or will simply be assigned to a strip and will begin when the first pool has concluded. This past 2018 Junior Olympics in Memphis, TN, Cadet Men’s Epee was flighted, so the first round of pools started at 8:00am, and the second one at 10:00am. If you are in the second pool, you have a two hour wait. If your fencer is a beginning fencer, chances are he or she will be nervous at the prospect of fencing in a tournament. Whether the tournament is large or small, if you can make the tournament the focus for the day, it can help your fencer feel more confident about fencing. This doesn’t mean focus on results or winning. This means try not to have other events competing for attention with a tournament, so your focus is not pulled away from supporting your child to worrying about whether or not you will be able to make the next event, etc. Another recommendation is to maybe plan a celebratory family dinner, or even go to dinner with other fencers after the event. Whether or not your fencer comes home with a medal, he or she will have new experiences to review, things to celebrate as well as learn from, and always a story to tell. Enjoy! Part One - Pools: Things to know before Pools begin-

How Pools Work Pools are made up of all of the fencers entered (and checked in) in the event, with the top seeded fencers each getting their own pools.

Pool Structure:

At the end of the pool bouts, each fencer is asked to review the score sheet and then sign his or her name. Referees can and occasionally do make mistakes. Make sure your fencer really looks at the sheet before signing. I keep track of all of Stafford’s pools in Notes on my phone and then show it to him to review before looking at the score sheet just to refresh his memory. The more your fencer competes, the more he or she will remember the bout scores. Your fencer should always shake hands with the referee after signing the pool sheet. Scoring out of pools:

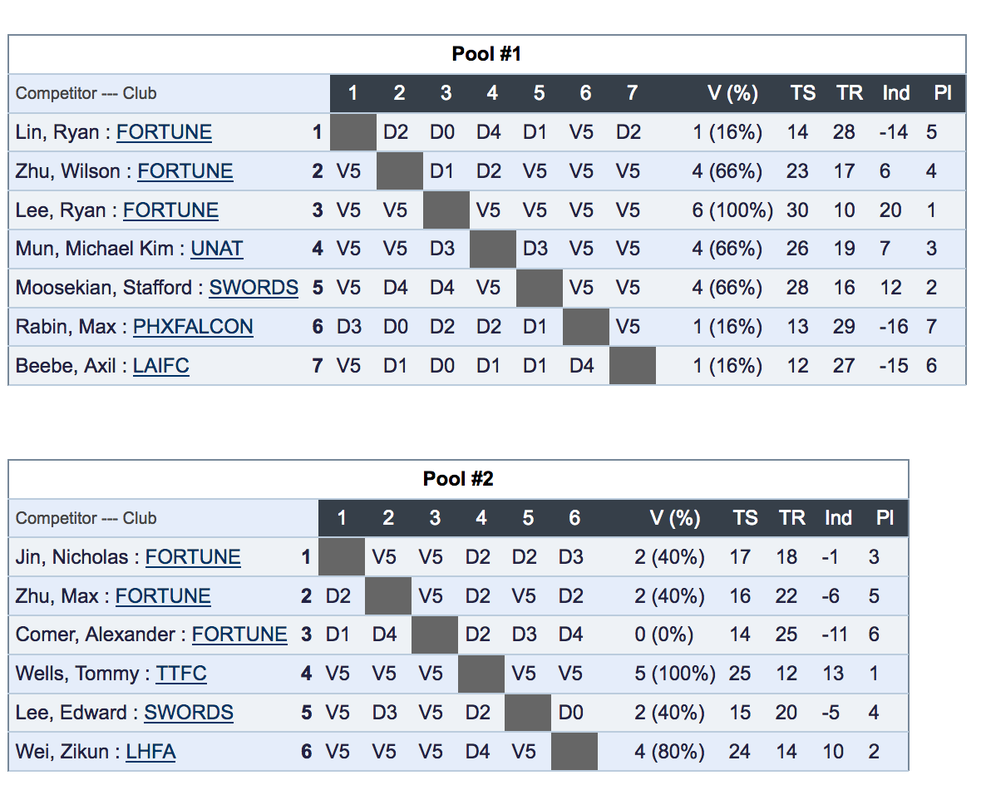

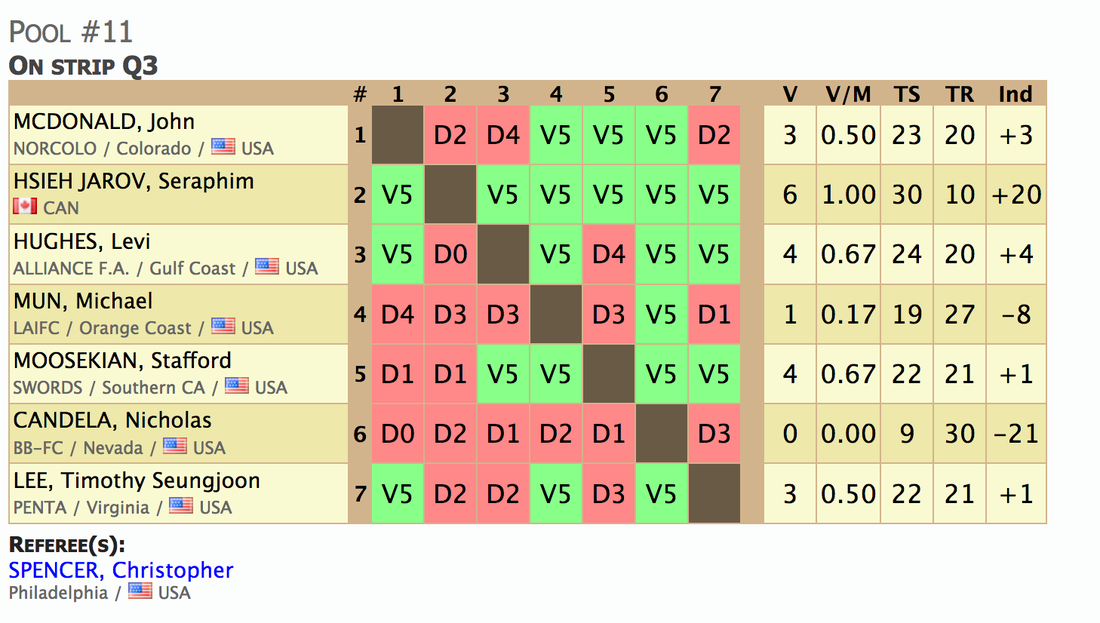

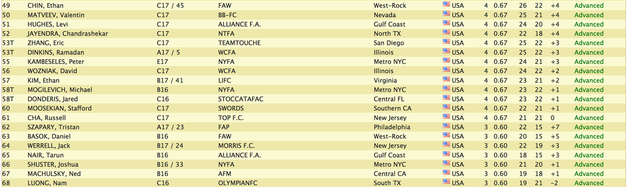

Promotion to the next round: In Y10, Y12, and Y14 events, 100% of the fencers are promoted to the Direct Eliminations whether in local, regional, or national tournaments. This way, younger, less experienced fencers are able to fence more and gain experience in a tournament atmosphere. In Cadet, Junior, and Division national events, the bottom 20% are eliminated and do not move on to the direct eliminations. Here are pool results for a smaller, local tournament: 13 fencers – 2 pools, one of 7, one of 6 First out of Pool #1 – Ryan Lee, who won all of his pools, scored 30 touches, and received 10 touches. So his indicator is 20 (30 – 10). First out of Pool #2 - Tommy Wells, who won all of his pools, scoring 25 touches and receiving 12, so his indicator is 13. Remember, Tommy had a smaller pool so though he won them all, he would come in behind the other fencer in a larger pool who also won all of his or her pools. So, seeding out of pools - Lee #1 and Wells #2 Who came out third? Three boys had 4 victories, Wilson Zhu (ind. 6), Stafford Moosekian (ind. 12), and Zikun Wei (ind. 10). You would think from the indicator that Stafford would have come out third – but- he lost two bouts, whereas Zikun only lost one. Remember one pool was 7 and one 6. So, though they have the same number of victories, Stafford lost two, so Zikun took the third place out of pools. Make sense? Here is another example: in the much bigger tournament, the 2017 Summer Nationals Cadet Men’s Epee Event, using Stafford Moosekian as an example: Stafford won 4 bouts scored 22 touches, received 21 touches. By the way, V5 means he scored 5 touches. You can win the bout V1, meaning with only one touch scored, which would change your touches scored number but not the number of victories you have. Stafford’s indicator is 22-21, so +1. If he had received more touches than he had scored, the indicator would be a negative number (like Michael Mun or Nicholas Candela in this example). Once the seeding from pools is posted, fencers have a few minutes to verify their indicator and seeding before the next round, the Direct Eliminations, begins. Stafford came out of pools seeded at 60. You can see the two boys who placed ahead of Stafford had the same indicator, +1, but because they scored more touches, they placed ahead of him. Tristan Szapery, because he had 4 victories but his indicator, at 0, is the lowest of those who earned 4 victories, brings up the bottom of the group who had 4 victories. The boy right under him had a higher indicator, but he only won 3 of his bouts, so he will be seeded just below those who won 4.

Once pools are done, take a deep breath. Your fencer has some time to relax, anywhere from 20 minutes at smaller tournaments to much longer if pools are flighted and your fencer is in the first round of pools. He should get something light to eat. Fruit, a sandwich, etc. Be sure she hydrates, as well. Gatorade or Vitamin Water help replenish electrolytes. Also, many fencers like to change into a clean t-shirt for the next part of the tournament - the Direct Eliminations. After the seeding is posted for the Direct Eliminations, your fencer has a few minutes during which he or she should start to warm up, do some stretches, maybe even do a warm up bout. Next - Direct Eliminations! One of the most confusing things to figure out, once your fencer is ready to compete, is how to find tournaments and how to know which ones to go to. Some children can’t wait to compete and some find the idea of competing intimidating at first. When the conversation turns to when instead of if, it is important that your child start competing at a level that is appropriate. You want to encourage him or her, and fencing against much better or more experienced fencers can be demoralizing, especially at first. Talk to your coach. Talk to your child. Before your child can compete in any tournament, he or she must have a USA Fencing membership. Most clubs have USA Fencing sanctioned tournaments that take part in the USA Fencing insurance program. You will be asked for proof of membership when you arrive at each and every tournament. You will also need a proof of age for your child at a tournament, until you are able to have USA Fencing verify the age, so be sure and have a copy of a birth certificate when you go to tournaments. Individual Competitive Membership costs $75 a year. Here is the link to sign up: This blog will not deal with specifics regarding earning points or qualifying for Summer Nationals or the July Challenge. Please refer to the USA Fencing website, as those specifics change frequently at the beginning of each year. There is a link to the Athlete Handbook at the end of this blog, for further reference. Events and Age Categories: (Y means Youth) Y8 - Fencers age 8 and under (these events are uncommon; usually events start at Y10) Y10 - Fencer age 10 and under, and so on through Y14. Cadet – Fencers age 13 – 16 Junior – Fencers age 13 – 21 Though here I use ages for convenience sake, USA Fencing uses the birth year as a determining factor for the age groups. Refer to the USA Fencing Athlete Handbook for the current birth years for each category. Mixed events mean boys and girls fence together. Basic recommendations for beginner fencers:

For new fencers, local tournaments are the best place to start. Many local clubs have “unrated” tournaments - these are typically tournaments for younger or beginner fencers. Some of the local clubs have a series of tournaments with fencers earning points each time they compete in one of the series. Those points are added together for some kind of prize at the end for the top points winner, typically a medal or trophy. Upcoming regional (and national and international) tournament information can be found on the USAFencing website at this link: Tournaments.

Local tournaments are great for new fencers for a number of reasons. Fencers face a lot of pressure on the strip, even at the beginning level. As your child begins to compete, he or she will learn a lot. He will learn how to win and how to lose. She will learn how to think on the strip and how to keep calm. If you have the option of having one of your coaches from your club come and coach, your fencer will start to learn how to listen and think on the strip. Not all coaches are willing to go to these tournaments, and they will charge a fee, so this is somewhat of a luxury, if even available. You can always ask. Whether at a tournament at this level, or at an RYC or SYC (detailed later in this blog) if your coach attends, your coach will also learn a lot about your child- how he or she deals with pressure and what has (or has not) been learned from all of those classes and private lessons. Once your child has competed in a few local tournaments and has achieved some nice results, talk to your coach about moving up to the next level of competition. Your coach is the best source for questions like this. Another thing to consider is the pressure your young fencer faces. Once you move up to regional tournaments (details in the next section) it will probably involve travel, whether a road trip, or a plane flight. Just the fact that you are disrupting the routine and investing in the travel, packing, etc., puts more pressure on your young fencer. Make sure he or she, and you, are ready. RYCs, SYCs, RJCs, RJCCs, ROCs, and NACs - What they mean and what you need to know. RYC: Regional Youth Circuit USA Fencing has divided the US into six regions. California is in Region 4. This region includes the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah.

Fencers from any region can compete in an SYC tournament. USA Fencing will only take the top result however, regardless of how many times a fencer competes in an SYC. SYCs are more competitive that RYCs and attract fencers from all over the US. RJCC: Regional Junior and Cadet Circuit These are regional tournaments for fencers who are Cadet or Junior aged. Again, the R means regional so make sure you are planning on attending an RJCC in your region. Fencers can earn points for the July Challenge at these events, and they are very competitive. ROC: Regional Open Circuit This is included here, just to give a basic understanding of what a ROC is. These tournaments are open to any fencers over 13 years old. Fencers can qualify to fence in the Division II and Div 1A events at summer nationals with points earned from these tournaments. Only older beginning fencers should attend an ROC as they will be fencing against fencers of all ages who typically have a lot of experience and are very strong. NAC – North American Cup The North American Cup Tournaments are a series of tournaments organized by USA Fencing (Y10, Y12, Y14, Cadet, Junior, Div I, Div II, Div III, Vet Open, Vet Age, Wheelchair, and Cadet/Y14/Junior/Senior Team). NACs rotate through cities across the country. You can find more info on the USA Website.

Summer Nationals All fencers have to qualify for this tournament. Luckily, USA Fencing wants to encourage young fencers to participate, so they have made the path fairly simple. Fencers in Y10 only have to compete in an RYC. Placing first or last, the result is irrelevant. If a fencer participates, he or she has qualified to fence at summer nationals. Take a moment to download the USA Fencing Athlete Handbook for much more detailed information on tournaments. Ready? Fence! Fencing Competitions - Recommendations for Beginning Fencers and Parents

Once your child starts competing, everything changes. In a great way. Your child is going to start to put into action the things he or she has worked on in classes and during private lessons. Your child will gain self-confidence, make new friends, and have some fun. Below are some suggestions to help make the experience a successful one, regardless of how your child does in the tournament. This is the first part of a series meant to help guide new fencers and families through the tournament experience. Later posts will explore how a tournament works (seeding, pools, DE's), travel tips, etc.. Getting There Being prepared helps you get out of the door and on the freeway (for some reason the tournament location always involves a freeway in California!) and helps your child focus on fencing. Typically, the calmer the parent is, the calmer the child is. Planning ahead by figuring out the route to take to the tournament and getting all of the equipment together in advance is a great way to avoid chaos in the morning, especially as events often start early. Here is a list of what you need for a competition: Requirements: Equipment (put your name on everything! Not just your initials, as someone else might have the same initials):

The Night Before:

Competition Day

Once check-in is closed, Pools will be announced. This posting might be online but should also be posted somewhere in the venue. Your child should find out which strip he or she will be fencing on, and proceed to that strip will all of the equipment (that has been checked at Weapons Check) and swords, and be ready to start fencing. Good luck! The next blog will detail the structure of tournaments - seeding, pools, and the direct eliminations. |

Tournament Fencing Needs

Mandatory: Additional Helpful links: USA Fencing National Athlete Ranking - Men's Epee National Athlete Ranking - Women's Epee Regional Points Standings USA Fencing Athlete Handbook SoCal Divison AskFred AuthorKathryn Atwood - Swords Fencing Studio. We welcome any questions and comments, suggestions for topics, etc. Categories

All

Archives

March 2019

USA Fencing Rules Book

|

||||||

Photo from daniel0685

RSS Feed

RSS Feed